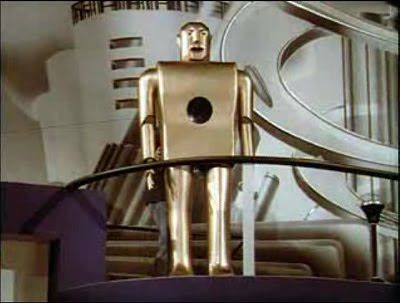

From the great reeking dumps rose Corona Park, site of the 1939’s World’s Fair and home – briefly – to “the world’s first celebrity robot,” Elektro. “Elektro the Moto-Man” began life as one of several different automatons built by the Westinghouse Electric Corporation in its Mansfield, Ohio laboratory.

Elektro could do no useful household chores or protect our nation in time of war, but no one had seen a real-life robot before – let alone a gleaming gold-painted gizmo in human form – and he became the star of the 1939 World’s Fair.

Though each robot reputedly cost Westinghouse hundreds of thousands of dollars, their feats of wonder were limited by a rudimentary technology. Elektro’s “accomplishments” included walking, talking, and smoking, i.e. rolling forward slowly, moving his head, jaw, and arms via the action of ordinary motors and chains, playing a 78-rpm record, and using bellows inside his head to puff a cigarette placed in his mouth by an assistant.

Elektro’s appearances at the World’s Fair were glamorous events. He was a steel and aluminum harbinger of humanity’s unlimited potential – or Westinghouse’s – and millions of people marveled as he spoke from his balcony (like Juliet! like the Pope! like Mussolini!) high above the crowds of ordinary citizens, some of whom brought their home movie cameras to capture their glimpse of the future. (N.B. Look for Elektro about 15½ minutes in.)

Soon Elektro was joined by a mechanical dog. Though “Sparko the Moto-Dog” seemed like more of an afterthought than real progress, he charmed just the same.

Millions flocked to the World’s Fair as the Great Depression shambled through its tenth year. Elektro seemed to embody Enlightenment ideals: the promise that set-backs were temporary, progress was assured, and the future was promising.

While we dwell on the prospect of our infinite perfectibility, flash forward hardly any time at all to 1940: the World’s Fair is bankrupt. The dream of the future has come crashing to an end. (According to a Pittsburg Tribune-Review article reprinted by the Westinghouse Museum, “A cartoon appeared in The New Yorker the day after the fair closed. There were no words accompanying the cartoon, only a sense of sadness at seeing Elektro and Sparko walking away into the sunset.”)

Elektro was crated, shipped, and stored at the Westinghouse facility where he was created. However, when the United States declared itself part of WWII (okay, Japan sort of declared it first), Elektro had no place in laboratories that had been turned over to the production of such military necessities as M1 helmet linters. (Did you know the poster of the “We Can Do It” woman making a muscle was made for Westinghouse employees during the war? Yes, it was.)

Westinghouse engineer John Weeks had worked on Elektro and decided to save him from the scrap heap, so he took the robot home for safekeeping. His son Jack was eight years old at the time and did what any boy would do upon discovering a gigantic robot in the basement: he dressed up Elektro and played with him.

As with many former stars, Elektro (and Sparko) hit the road for appearances at department stores, tourist attractions, and theme parks such as the Westinghouse exhibit at Pacific Ocean Park (where he was painted silver). At one point the Elektromobile was in a car crash and Elektro’s entire torso had to be replaced (and then he was painted copper).

To his credit, Elektro also visited hospitals and nursing homes; yet year by year audiences saw him less as an awe-inspiring engineering wonder than a kind of quaint clanking relic from a drive-in movie. As happens to many former celebrities, Elektro found himself cast as the opener for a novelty act when he and Sparko were dispatched to promote the movie The Day the Earth Stood Still.

After several years of life on the road, Elektro showed up on YOU ASKED FOR IT, a television program featuring viewer requests for nutty stunts and where-are-they-now appearances by celebrity actors and robots.

“I am Elektro, mightiest of all robots,” he tells the studio audience, “I was created by Westinghouse Laboratory. I am 7’6” tall. I weigh 260 pounds. My brain is bigger than yours. It weighs 60 pounds. I can do many things. If you use me well I can be your slave.” (A slave? Elektro the Moto-Man, a slave? We’ve just got through WWII, we’re about to tackle Civil Rights, and we’re romanticizing slavery, Eisenhower America? Everything they say about the 50s was right.) The “Skippy All-Time Award” our announcer mentions is named after the show’s sponsor, Skippy peanut butter, so we can be pretty sure Elektro is blowing up a balloon instead of smoking a cigarette because kids are watching. Dire! (Of course, our own times are responsible for Roxxxy – “sex robot“and saddest invention in the world.)

But it’s back to the sad tale of Elektro, who shows up once again in an unlikely venue – this time in the 1960 film “Sex Kittens Go to College.” The SKGtC trailer is readily availible online and in case you forget what it’s about or see it under the title, “Beauty and the Robot,” the trailer reminds you nine (9) times: it’s about sex kittens. Elektro underwent surgery for his role: the porthole in his chest was inexpertly plugged and a square hole was cut for a speaker. Not only is he typecast as a robot named Sam Thinko who is, for the most part, relegated to the background and given corny interactions with actress (pronounced “breathy jiggler”) Mamie van Doren, poor Elektro spends the movie broadcasting pseudo-sexy dialogue that writes checks his aging circuits and gears can’t pay.

But here’s the bit that captures the average blogger’s imagination and holds it hostage: there is a scene in which Elektro appears with a chimpanzee and stripper doing what the average blogger likes them to do best, i.e. the chimp wears human clothes and the stripper takes off human clothes. (See the sadness of Roxxxy, above.) (Ed. note: see the clip at this link. which features Elektro/Thinko’s racy “Dream Sequence” which was only used in the European Cut of the film. Or watch a “safe for work” clip below):

Just when you think Elektro is fated for the crusher (and you’d be justified thinking so, as he was decapitated and his head given away to Westinghouse executive Harold Gorsuch, a moto-man project veteran, when he retired), Jack Weeks comes on the scene.

You may remember Jack Weeks as the eight-year-old who played with Elektro in his basement. Jack became an engineer like his dad, and when he happened to find himself at the screening of a middling sex comedy, he recognized Elektro in the midst of the sex kittens and vowed to save him from a fate worse than B-movies. (The story of his search for Elektro’s body parts is as compelling as that of Isis and Osiris, and though he keeps the original blueprints under lock and key, you can pore over the schematic that shows the bellows that enabled Elektro to “smoke” and blow up a balloon.)

It seems everyone takes a proprietary interest in Elektro and we can’t help hoping for a happy ending. Even Jack Weeks let himself hope that Elektro, newly restored to his former dignity, would end up in the Henry Ford museum alongside our nation’s other early ingenious inventions.

Elektro’s history is a sad one and the *spoiler* will not come as one at all: the moto-man (and his moto-dog) never made it to the Henry Ford museum, as Jack Weeks – and others wished.

Sparko, of course, hasn’t been seen for decades and the Mansfield Memorial museum (“We are the permanent home of ELEKTRO, the Westinghouse robot built for the 1939 New York World’s Fair Oldest Surviving American Robot in the World.”), which is the home of Jack Week’s restored Elektro

displays a resin fiberglass painted facsimile to crowds so sparse the doors are only open on weekends (but not in January.)

For a brief while, models of Elektro and Sparko appeared in a Japanese robot museum, but that went out of business. Pittsburgh also plans to exhibit a model Elektro (and Sparko). We’ll see.

Elektro is the only robot of his design. There was never another like him. Though his life’s history has been written about, talked about, viewed, and witnessed in person literally millions of times, as with Elektro himself, many parts are missing, presumed lost.

** written for the January installment of the live show KEVIN GEEKS OUT, where the theme was “Visions of the Future.” M. Sweeney Lawless is a writer/performer whose work appears in the upcoming Any Body’s Guess (Andrews McMeel, 2010) and The Lowbrow Reader Anthology (Drag City, 2011) She is also a producer for KEVIN GEEKS OUT.

Thanks to Elliott Kalan and Kevin Maher.

Additional Elektrobilia for your Elektrophilia:

A tenuous Elektro-Marx Brothers connection

http://minniesboys.blogspot.com/2009_07_01_archive.html

Have you seen Sparko?

http://www.popcitymedia.com/innovationnews/innovation1105.aspx

http://jcwinnie.biz/wordpress/?p=1234

The rise and fall of Elektro

newscientist.com/article/mg20026873.000-the-return-of-elektro-the-first-celebrity-robot.html

Elektro and Sparko make the Top 50

1939-1940 New York World’s Fair History

Images of Elektro – both candid and canned

Here is an Elektro etching

And the same image on one of the tablets near the Unisphere (scroll down)

1939 World’s Fair Souvenirs – including an Elektro pin!

People can’t resist writing fictional biographies for Elektro

davidszondy.com/future/robot/elektro1.htm

Listen for “I am Elektro” and dance to his braggadocio: “My brain is bigger than yours”

ROAD TRIP – Go See Elektro! (but call first)

Mansfield Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Building

(419) 524-2491

N.B. the museum is open limited hours and too poor to have its own web site

Scroll down for an account of a road trip and more facts from Elektro’s history

Elektro – Corporate Shill

May 1, 1939 Hammond Times (Hammond, Indiana) thanks to paleofuture:

July 2, 1956 San Mateo Times ad, thanks to paleofuture:

Valerie Sobczak

I saw Elektro at The Henry Ford Museum this week! He was there as part of a special exhibition on the World's Fairs of the 1930s. Jack Weeks' dream came true after all.